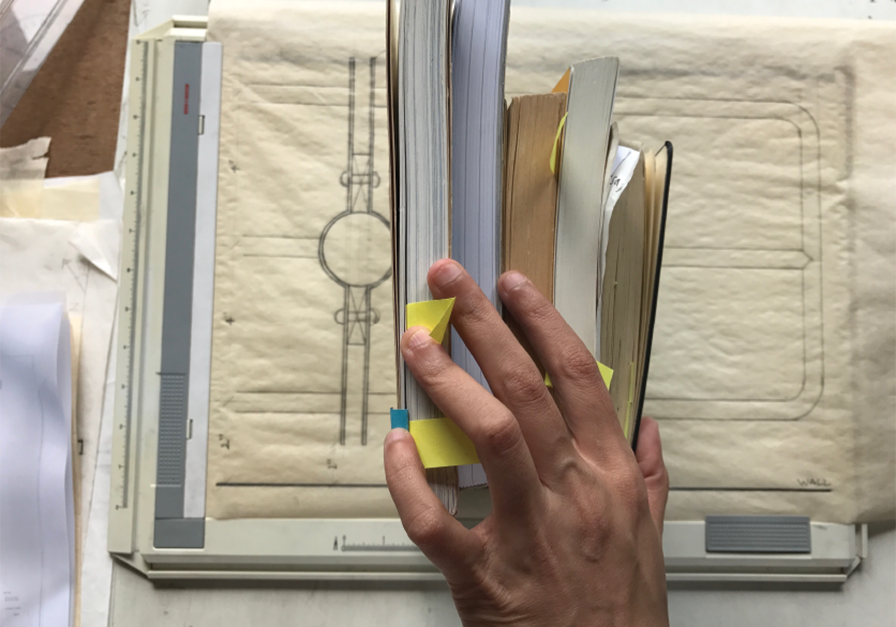

"Technical and architectural drawings can co-exist. In the speed of thinking, the mind is trying to record an instrumentality; how something works or is made. is has carried through to my subsequent way of working"

‘Drawing to Find Out’ is an annual curated column on drawing in architecture and the techniques and ideas therein. In its fifth edition, Matter interviewed Shubhra in an attempt to decipher the draftsmanship cultures, their relationship with the design process and the way in which they inform her practice.

The full editorial and video can be found here.

An excerpt from the conversation, on mentors and attitudes in drawing:

More than mentors, I will talk to you about drawings, and acts of drawing, that are now a part of my life and those that have made an impression on me over the years. Some of this we have already been through in previous questions. Some were for sheer pleasure; a play, really – somebody starts communicating with you through drawings and diagrams, you tend to want to reciprocate. Childhood was also a lot of comic books, books with illustrations, graphic novels. Comic books that contained very fine diagrams of aeroplanes and ships, like the Commando series. Curiously, we did a lot of Origami – which was a world of instructions through diagrams about paper folds and cuts (which I love, even now). Sometimes I feel we should do construction drawings that way – step by step instructions! I love IKEA drawings, very frugal but precise. No wonder that Billy bookcase gets made in spite of the woeful skill levels of the person putting it together!

I do not like drawings that obfuscate. Those that look complex, but are merely effectual — things put together to represent complexity picturesquely. There can be a lot of inauthenticity in drawings, and I have a great impatience with that. There was a period where drawings were made with a whole bunch of “regulating lines,” or urban studies with lines supposedly extending meaning from one point to another so that when you are finished with the drawings it resembles those Mikado games with a bunch of sticks scattered that you then end up having to pick up, one by one.

Diagramming, though, I was curious about. I loved old drawings of plants and animals, which were beautiful, carefully made and you could see that people were observing every minute little detail with a great degree of accuracy; you could sense that they were trying to understand the world around them.

During architecture school, I do not remember much around drawing; there were other things I remember learning. Most significant were the structural exercises where we had to build something which was tested until it failed. Those memories are etched in my brain, because, you could not escape. If your model failed, it failed. Often spectacularly and prematurely. It was the kind of accountability that my drawings could slip past (or so I felt). The structural models or the technical drawings of endless brick courses and intersections did not allow for these slippages and distractions, and for this, I remember them much more.

My father’s studio, in our third semester – here we talked about and worked with drawing differently. Learning about space-making through drawing. How shadows have a mass; and the physicality of drawing something really dark, with graphite or charcoal, and then to deduct from it with a kneaded eraser in order to find spaces, mould spaces. My father’s drawings or Kahn’s drawings — investigative, iterative drawings in charcoal and graphite — these are very dear to me. Corbusier’s, as well. But there is a familiarity here carried through from childhood, and I do not know how to distance myself from them as yet. So I have left them alone, for now; but they are always there, as part of my general milieu.

The drawings that significantly affected me, in opening up the possibilities of architectural drawings, how architects drew and perhaps thought, were those of Enric Miralles. In the early 90s, when I first encountered drawings of his early works done in collaboration with Carme Pinos, I felt I had seen something quite original. They were drawings that made me stop, and look at them. Initially, this was also because I was trying to make sense of them. But unlike certain other, perhaps, more celebrated drawings – say, Zaha Hadid’s drawings for the HK Peak Project – these ones I could not walk away from; they somehow held my attention. He seemed to be turning Corbusier’s Plan Libre inside-out. In his drawings, you did not quite know where a building ended and the landscape began; you could not quite comprehend boundaries and thresholds. The more you began studying his drawings, the more you began to realize that those were some of the conditions where his investigations were, which is why he was making these kinds of drawings. At that time, I was terribly attracted to such a style of drawing, to the extent that although my drawings were different, I would imitate his font style. Thankfully, this lasted about six months and soon one realized that you may imitate styles, but one cannot imitate another’s thinking.

I became familiar with the drawings of Lewis Tsurumaki Lewis (LTL), and the early drawings of Diller + Scofidio while at Cornell. In each case, instrumentality was front and centre — the instrumentation of drawings anticipating the mechanics of construction. It was not just about the function and use (of a drawing), but a certain kind of alchemy where there was a preoccupation of how things come together, and remarkably, there was a strong presence of the hand (and of making). They talk of slowing things down, erasing things and drawing over, traces. LTL has written about this form of “overdrawing”, an active exchange, a back-and-forth, between disparate mediums and methods. As a result, there is a lot of movement one can perceive in these drawings. This had a profound impact on me, especially because this was at a juncture where people were beginning to talk about the computer versus the hand, an argument that I have always found a little facile. Invariably, the hand-drawing camp tended to be a little more romantic about things yet tended towards abstraction, while people at the computer end of things tended to be more effectual, pursuing a kind of realism. So there were inherent contradictions between these camps. The drawings of LTL or D+S seemed to be able to disregard these binaries and were looking at ways of synthesis.

There has also been an appreciation of Glenn Murcutt’s drawings, specifically his construction drawings. The fact that his was a singular practice, and that the scale, pace and scope of his practice, and the manner in which he drew, was rooted in the body. It was framed by what he could do, personally. And this is where hand-drawing became very relevant to me, because it was an expression, not of production, but that his body was inhabiting his practice. That the drawings he made were somehow regulated by the limits of his body.

In all these cases, the drawing as an artefact is not so much a representation of thought but makes one a witness to acts of thinking and making. I learnt, in my post-Miralles obsession phase, that you could never draw like somebody else. When you do not know why you are drawing, you can end up imitating others; I have done so as well. Perhaps there is a notion that diligently imitating that which inspires you, you might imbibe something in the process. But that does not quite work, does it? Because there are so many layers of thinking and investigations, the way you ask questions within a context- you can never design, or think like somebody else and therefore you can never draw like them either. At best they can open up ways of thinking for you.